I have translated for a fascinating website in Naples, Italy started by senior speleologist, Fulvio Salvi, for many years. It deals with the spelological wonder called the "sottosuolo" or underground of Naples. I lived in Naples years ago and began a lifelong fascination with the gigantic quarried sandstone caverns, tunnels, Greek and Roman tombs and aqueducts, and passageways all forming a "parallel city" beneath the bustling streets of the ancient city above. Jaw-dropping sinkholes like the one below are not uncommon because of the city rests upon an astounding maze of voids below.

This is a quick look at a typical sampling of the wonders that honeycomb the earth beneath the ancient city of Naples, Italy. The durable and easily worked 'tuffo' or yellow tuff sandstone was ideal for digging deep aqueducts from springs in the outlying mountains down into the city. The Greeks first did this some 2,500 years ago, and over the centuries other aqueducts were dug in the sturdy tuff. This wonderful sandstone made of hardened expelled volcanic ash and lava over the millennia is also a perfect construction material, and huge palaces and villas were built from large blocks of this wonder stone quarried from ever widening bottle shaped cavities beneath them. The sloping sides of the bottle shaped quarried void maintained the structural integrity of the ground beneath the huge buildings. The cavities were then cleverly used as huge water reservoirs some 30 to 40 meters below ground. Diversionary tunnels were dug from the cavities to aqueducts filling the reservoirs, which were lined with lime. This provided a ready supply of fresh water to the buildings above. Other well shafts were dug to allow access to the water reservoirs by the public within the early walled city. A typical quarried cavity some 30 to 60 meters below the surface is seen below:

The photos below are typical of what our Naples urban speleologists continue to find year after year. Paleochristian catacombs were created "in negativo" that is to say support columns and chambers as well as burial crypts were carved into solid tuff creating rooms and chambers that stretched into thousands of cubic meters of excavated space. The voids, cavities, tunnels, aqueducts, and passageways conservatively occupy an area beneath modern day Naples equal to three times the size of the Vatican. Only a small percentage of the maze has been explored and mapped!

So, let's take a quick look at photos, by senior president emeritus of the Italian Southern Speleological Society, Engineer Clemente Esposito. Photos that have been taken over his more than 50 years of exploring the mysterious marvel called the "Sottosuolo" of Bella Napoli. Scroll down, and down . . . I bet you are going to find this interesting!

Earliest Examples Dating from Paleochristian Times

An example of digging "in negativo" into the solid tuff, seen in the intricate construction of the paleochristian San Gaudioso Catacomb. It is typical of those dating between the 2nd and 9th century A.D. This one is accessed from a small passageway in a 17th century church!

Clemente is among the first to discover Greek Hypogea similar to this

one . . . burial crypts dug deeply into the yellow tuf which still have

amazingly intact frescos and decorations dating from paleochristian

times.

Excavations by the famed Naples Archeological Museum have revealed an entire Greco-Roman city street. This is Roman construction built over Greek ruins. This is a bakery oven, part of an entire street lined with similar shops which lies beneath the San Lorenzo church in the ancient original historic city center. Greeks built walls by stacking carefully fitting stones. Romans used cement, creating masonry walls with the characteristic diagonal 'diamond' shaped tuff block masonry.

Aqueducts from 2,500 Years Ago!

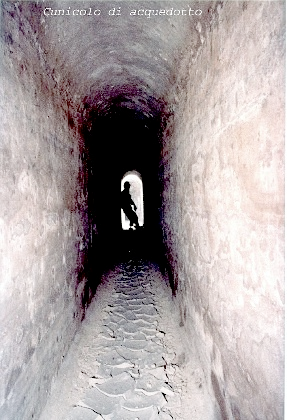

The first aqueducts were dug by the Greeks some 2,500 years ago. This particular section is quite large compared to the snug fit of many we now use to navigate beneath the city. The pick marks from Greek slave laborers are still clearly visible today.

This is a typical example of the immense cavities that were used as reservoirs, complete with access sidewalks for maintenance. These snake for miles beneath Naples.

And here's how we drop in for a visit and a look around! Old well shafts on the surface belie what is below. Note the mountain of debris, typical of what clogs up and blocks many of the cavities and accessways. Unfortunately the surface opening shafts are simply considered to be the world's largest trash bin in the minds many folks in the city.

World War II Air Raid Shelters

In WWII, well shafts were enlarged and spiraling stairwells constructed under orders of Mussolini for public entry into air raid shelters 30 to 60 meters below the surface in the immense quarried caverns which were outfitted with lights and even showers. Some even had airtight doors to counter feared gas attacks.

Here is another example of stairs descending into the shelters below. Michael Quaranta, another senior speleologist, conducts daily tours of a huge air raid shelter beneath the old Spanish Quarter. Scuffed, stained, well worn steps attest to the nightly descent by hundreds of fleeing Neapolitans as the air raid sirens began to wail.

Entire families huddled together as allied bombers rained bombs down upon Naples. Many, many families came back up to find their entire neighborhoods destroyed. They would grab what they could then returned to temporarily live in the caverns below.

Cavities were enlarged and interconnected with large tunnels like the one above, offering safety to thousands. This image is frozen in time with the old benches where refugees sat, now slowly crumbling under their own weight as the decades pass after WWII .

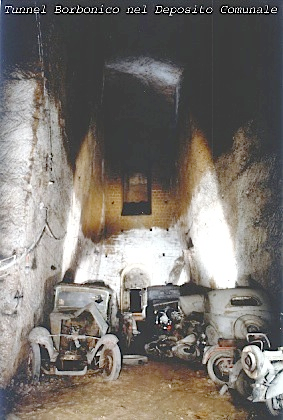

During the reign of the Bourbons, a huge tunnel was dug from the royal palace through the tall hill dividing the city. It was to a quick escape route to the bay on the other side of the city. It was large enough for horses and carriages to move through. Parts of the tunnel were used as an auto graveyard decades ago. Today this amazing Royal getaway tunnel can be visited with tour guides!

Having huge quarried caverns and tunnels beneath the city takes a toll today, with huge washouts and cave ins like this one not at all uncommon after torrential rains all over Naples and surrounding area!

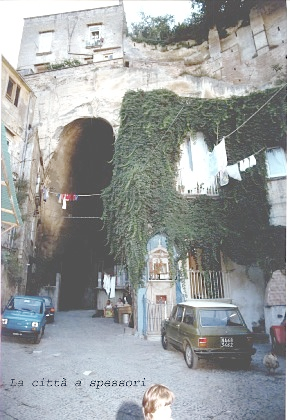

Today, entrances to huge cavities and tunnels are used for private storage, improvised parking and even auto repair shops. Windowless homes are dug right into the soft yellow tuff volcanic sandstone.

Bookmark our web Naples site: http://www.napoliunderground.org/index.php/en/

We hope you have enjoyed this brief glimpse at the "Sottosuolo" of Naples. Below is a more in depth history of the Napoli underground which you may enjoy!

The Other City

I present this translation as part of an in-work project I have undertaken from the original Italian. The

author, Antonio Piedimonte, is a professional who is part of a group of

young intellectuals who form a loose cultural group known as

"Intra Moenia" which means roughly "Within The Walls"

referring to the original walled city of Naples. I have been down in

the caverns and tunnels beneath Naples with various urban

speologists, notably Michael Quaranta, and have developed quite a

library of research materials, including a rare copy of a special

illustrated study done in the 60's by the City of

Naples mapping all the tunnels, caverns and passageways discovered to

that date. Read this and I think you too, will become as fascinated as I

am with the mystery and lore hidden beneath Naples in its

"Sottosuolo"!

This is a trip into a parallel city down below the modern day city of Naples, Italy. A silent city where the ancient volcanic sandstone, or tufo, "breathes," and time seems to stand still. Homer and Virgil accompany us through an incredible network of subterranean passageways, caves and streets that are carved from legend. A history that has not really yet been written. A history still waiting to be told. This is the "sottosuolo" or underground of Naples.

Ancient sacred ritual burial crypts and hypogea, Grecian caves, Roman aqueducts, medieval tunnels, secret Bourbon tunnels and passageways: just four historic footsteps from the past, and thus into the future of the underground of Naples. The Naples underground, one of the largest and most extensive anywhere in the world. The last mystery from the Parthenopeans, the first Neapolitans.

Running beneath the city are millions of cubic meters of space, excavated and reworked for almost three thousand years, work too often abandoned. It is today a result of neglect, as well as devastation from natural and man made causes. Millions of cubic meters of black void cut beneath almost every neighborhood and quarter of Naples to varying depths. It is a completely distinct subterranean city, for the most part unknown, that safeguards the extraordinary secrets, both observable and invisible, of all that has happened through the millennia. . .here in the shadow of Vesuvius.

It is a strange city hewn into the city’s foundation of volcanic sandstone. No one knows its dimensions. Speologists exploring the huge network over the past thirty years have calculated that at least 60% of the population lives and works above the cavities. Only in the Stella district have some 62 manmade grottos and caves been recovered for present day use for an area totaling some 160,000 cubic meters of underground space. A rough equivalent of four square meters for each inhabitant of the Quarter! Another 86 caverns are beneath San Carlo all’Arena; 85 in the Avvocata district, 34 in San Fernando and others in the Chiaia district, 32 beneath San Lorenzo and 28 under Cape Posillipo. And these are merely ones from the existing census of underground cavities.

In all, from the end of world war two to the present, some 700 cavities consisting of tunnels, galleries, caves, secret passageways are known so far. Greek caves, Roman and Bourbon tunnels, catacombs and natural grottos make up a total of a million square meters of underground space. Recent and continuing explorations by a group of enthusiastic experts and devoted cave explorers indicate that much more remains to be discovered. Right beneath our feet there remains, conservatively, another two million square meters of unexplored, undocumented spaces.

The future of this enormous underground space, dug for the most part during early Greco-Roman periods and expanded and "touched up" over the centuries, remains unknown. These elaborate excavations remain practically indestructible owing mainly to the presence of an ideal material for tunneling and creating enormous caverns: the famous Neapolitan yellow "tufo", a workable but durable sandstone formed through geothermal and volcanic activity 13 million years ago.

Hundreds of these caves have been transformed little by little over the years, but in the mid 1940’s they were hurriedly put to use as air raid shelters. Of 210 air raid shelters used during the war, all were created by altering ancient caves, and enlarging Roman aqueducts and tunnels to connect various caves and enormous cavities beneath the city. Less than half of them can be located today because of blocked access, urban growth and other difficulties. Just in the crowded Spanish Quarter alone, above Via Roma for example, there still remains to be rediscovered, a huge air raid shelter that housed some 20,000 people during the worst of the bombing.

The oldest cave discovered to date is an ancient sepulcher some 4,500 years old in the Materdei district from the "Cultura del Gaudo." If we exclude the well known catacombs, caves and cavities with archeological significance, the hundreds of other underground areas catalogued to date by Neapolitan speleologists, which has given birth to a new ‘Urban Speleology", are mostly inaccessible and in an awful state. Forgotten for decades, these mysterious spaces have suffered the ravages of time, neglect by man and institutional indifference.

It is not unusual to discover conduits, aqueducts and cisterns from Greco-Roman times now blocked, completely filled with refuse thrown down the old well shafts.

This ancient system until the end of the last century furnished potable drinking water to the entire city. Tons of waste, garbage and refuse dumped into the voids below in recent years has caused dozens of underground fires which have burned out of control with tragic consequences.

An example is the January 1982 fire, which produced toxic smoke that seeped into the drains and foundations of the old "bassi" or slums in the Spanish Quarter behind the fashionable Via Roma. Deadly fumes entered one squalid hovel through the drains, killing an old man in his sleep. Also on the 7th of June, 1979, a dramatic fire flared up beneath the Gradoni di Chiaia.

It all started when a woodworker and carpenter who had used an old well shaft in his shop as a place to dump wood shavings, sawdust and other material made a paper torch to look down into the shaft. The torch was accidentally dropped inside. An insidious smoldering fire resulted and later erupted beneath the entire quarter releasing acrid and noxious fumes. Thirty families were evacuated for more than two weeks. City firemen, along with volunteers from the Naples Central Speleological society searched the extensive underground maze in search of the source of the fire and suffocating smoke.

It was finally located and extinguished the 22nd of June. On this particular occasion, the speleologists, as has happened before, rediscovered the huge vaulted cavity beneath the narrow alleyway of Sant’Anna di Palazzo which was used as an air raid shelter. It is one of the few now open to the public for regular guided tours.

But carelessness and disuse don’t only cause fires. In the recent past there have been repeated anxious instances of cave-ins, landslides, and sinkholes in many parts of the city. These disasters have killed and injured people and, for a brief moment, refocused the attention and concern of citizens upon "the other city". One of the most recent bizarre incidents took place just before this book went to press. An older married couple living in the Via Santa Margherita Fonseca had a rude awakening. While asleep in their bed, they, along with their entire bedroom plunged, with no warning, almost 30 feet into a void beneath their home. Miraculously, neither was seriously injured.

There exists a strange sort of forgetfulness, almost a kind of psychological repression that seems to have stricken the average Neapolitan citizen and city administrators. A frame of mind so typically Neapolitan, which reflects a Jungian reflex to maintain a mere "shadow of conscience". This results in the blocking out of any true consideration of the worth and possibility of utilizing the massive underground area to the public good.

So the situation merely becomes more shameful. It is indeed difficult to imagine, but we have unwittingly turned our backs on ‘the other city". Among the various theories as to why Neapolitans have adopted this mind-set, an old scholar suggests ancestral fear. He cites the Apocalypse, ". . .and they were given the keys to the well going down into the abyss; they opened the well, and from the well issued forth smoke and indeed the smoke blocked out the sun, and consumed all the air outside."

Psychoanalysis, religion, anthropology all would take too long to analyze and, indeed, would be out of place for the purposes of this little book as a means of explaining the strange rapport between the Neapolitan citizen and the "submerged" part of their city. For the Neapolitan the "other city" is part of the collective imagination, part of the city’s many symbols, signs, and much more, which invites a deeper investigation of the city’s "dark side."

For the present, however, we can only wait and keep track of the scandals, the continuing disasters and the silence of the guilty. There are a few exceptions. In some parts of the city, the old Greco-Roman underground water system of aqueducts and cisterns was integrated into a newer system built in the 1600’s. This combined system was used until around 1885, with every house and business in the city using individual well shafts connecting to underground cisterns or reservoirs below. To this day, many old pipes laid inside these ancient tunnels and aqueducts are still in use, but are in a horribly deteriorated condition, a situation that every modern day Neapolitan should be ashamed of.

Among other rare modern day uses of the immense underground network we can only count a couple of parking garages for cars and buses, a theatre for film and stage presentations, which is now closed (the former popular Metropolitan Theatre), and various caves and cavities used as warehouses. Recently, several old grottos and caves have been opened inside the Sant’ Antonio ai Monte public park. As for the rest, after years of debate, contention and political posturing, Naples’ huge archeological, historic and environmental resource remains abandoned in its own silent world.

Or it is claimed as the preserve of criminals and shady speculators, like this case which happened a few years ago: Police discovered a sophisticated underground hideout in the infamous Forcella district, near the central train station. The notorious "Stolder Clan" had set up a drug laboratory in one of the underground caves. The "laboratory" was connected by a network of escape tunnels and passageways, all of which ultimately connected directly to the inside of the mob boss’s house!

To combat this particularly Neapolitan type of subterranean mob activity, police have organized a special task force and underground "blitz" squad. During the 1994 G-7 meeting of world leaders in Naples, secret service agents engaged dozens of local experts as well as the police "blitz" squad to complete a sweep of the areas beneath various G-7 conference meeting places. For days they combed the complex of passageways but found no bombs or explosives. They did, however, find an ancient conduit with potable drinking water beneath the gardens of the Royal Palace.

II - History and Tales

The trip from ancient history into today’s news in Naples is often very brief , as the "sottosuolo" is so much a part of Naples’ continuing history. To cache weapons, hide men and stores one need only take a page from history and the tactics of the Byzantine General, Belisario. In 536 Belisario laid siege to Naples using the complex of aqueducts, passageways and tunnels to sneak his men, horses and weapons into the very heart of the city. In Neapolitan Legends and Stories by Benedetto Croce (which has recently been republished by Adeiphi Press) this same method of surprise attack reportedly was used by Alfonsa d’Aragona in 1443. This account is also found in the New Guide to Naples published in 1881, in which the author explains that the story is "even the more enjoyable because it seems so fantastic, yet is historically accurate". The account details Alfonso d’Aragona’s final success in conquering Naples after a long and unsuccessful attack from the outskirts of the fortified city. He was finally able to breach the city’s defenses thanks to the help of two master stone masons, "Aniello and Roberto". The pair, familiar with the "sottosuolo", showed the attackers a tunnel which ran under the city and exited via a well shaft which was located inside the shop of "Maestro Citiello, tailor" on Via Santa Sofia (not far from the Capuano Gate).

After the conquest of the city, and to prevent others from using the same tactics, the King ordered the well shaft destroyed and sealed. He further instituted a Knight's Guard Corps. Comprised of Knights, they were charged by their King with exploring the "secret city".

Under the rule of the Aragonese, the city underwent orderly urban growth which had an inevitable effect upon the city’s underground. The yellow tufo, the durable volcanic sandstone, was removed for use in constructing the grand palaces and apartments and other buildings. The excavation continued through the following centuries and was particularly intense during the rule of the Spanish Viceroys. Under the Spanish the excavation was became a rape of the valuable underground resource. The caves and cavities multiplied at an indiscriminate, uncontrolled rate. The growing honeycomb being created beneath the city aroused the concerned the royal leaders. They began issuance of a series of edicts prohibiting further excavation in certain zones.

Among the first of these "zoning restrictions" issued in 1615 and 1688 were the hills of the Vomero and San Martino, which overlook the city. These were followed by similar restrictions in the edicts of October 1781 by Ferdinando IV di Borbone. Then in 1850, Ferdinando II instituted a city building commission which placed the problems of the hollowed out underground as one of the most serious of the city’s problems. This alarm bell has continued to sound to the present day without stopping.

Georgion Mancini, in his book, "The Mysterious Sebeto" (published in 1989 by Ii Quartiere Ponticelli) retraces the story of the mythical river Sebeto, and details the exploration of the ancient underground water system in 1560 by the famed architect, Pietro Antonio Letteieri.

After spending four years painstakingly mapping and tracing Naples’ underground he wrote, "I can say with certainty that it is a huge shame not to revive this admirable and stupendous work". Letteieri, who had been charged by the Viceroy of Toledo with finding a new water source for the city, at the end of his investigation, presented a detailed project complete with a budget proposal for the cost: 2 million Ducats.

Interestingly, the routes the architect laid out were the same as those drawn up some 1500 years before, those commissioned by Roman Emperor Caesar Augustus to build the early city’s aqueduct! An imposing work, and one referred to by all major scholars and writers through the centuries as they chronicled the history and growth of Naples. These include Falco, Summonte, Capaccio, Celano, Savoia di Cangiano, Campasso and many, many others.

More than 70 kilometers in length, the water system began at an artificial basin fed by a reservoir from the Serino and connected Neapolis, (Naples), Puteoli, (Pozzouli), ending at Baja, (Baia) where it supplied the huge reservoir which served the Imperial Fleet at Miseno: the "Piscina Mirabilis" or "Wonderful Pool". The largest of its kind from ancient times, the Piscina Mirabilis remains in amazingly good condition today. It can be appreciated in all its massive glory by making an appointment ahead of time with the elderly custodian who lives at number 16 Via Greco in Bacoli.

With a system of tunnels and arched elevated canals, (like those visible at Ponti Rossi) this extraordinary work of hydraulic engineering brought water to the city and its buildings, where it was distributed almost entirely underground. Well shafts and tunnels which connected the buildings with deep cisterns multiplied with the continued construction of other aqueducts, in particular the so-called "del Carmignano", completed in 1629. This work was improved and expanded in 1770 by Ferdinando IV by combining it with the Carolino aqueduct built by his father, King Carlo III.

But by far the most famous exploration of the city’s underground is that undertaken at the end of the last century by a young, adventurous Neapolitan engineer, Gugliermo Melisurgo. His two year intensive study is detailed in a book published in 1889, titled "Subterranean Naples. Topography of the deep water network of canals, contributing to the study of the Naples Underground’. (This work was reprinted a few years ago by Colonnese publishing house.)

Melisurgo was a small "Indiana Jones" before his time. Soon after getting his engineering degree at 20 years of age, Melisurgo was directing work on the construction of a railroad bridge across the Sinni river in Basilicata. His adventure into Naples underground began after the terrible cholera epidemic of 1884. The city had hardly begun to use its new pressurized water system when engineers found countless instances of sinking and cracking. The emergency thrust the young engineer into the role of head of the city engineering office for "study of the ancient aqueducts". (today the city has a complete ‘Departamento di Sutosuolo’ or "Bureau of the underground")

The hard working young Melisurgo quickly concluded that the principal problem was "the ignorance of the topography of the subterranean city" and he quickly decided to fill in this void of ignorance. "No sooner said than done," the preface of his book begins, "We began our first trips into the maze below. (he was accompanied by a plumber named Nunzio Esposito) Two years passed before we finally finished our work. Winter, summer, we were naked from the belt down because we were forced to make long treks through narrow tunnels and aqueducts where water still runs in depths varying from ten centimeters to half a meter. Melisurgo continued, "We dressed in wool jackets, regardless of the season, underdrawers and short pants with nothing else but a tallow candle and a walking stick." Melisurgo and Esposito went down into "this other city that exists below", crossing through canals and tunnels of the ancient maze. The first aquaduct studied was the so-called Bolla aqueduct, built according to the young engineer by the Greek Cumani, "even though there remains some mystery as to its origins".

In the meticulous diary which young Melisurgo kept, he described his initial sensations after descending into "the strange world below, having the city above you... in other words, first blindness, then deafness and then slowly becoming accustomed, the eyes adjusting and the marvel of the senses." Melisurgo was accompanied on his descents by an experienced pozzaro, one of a legendary group of workers who kept the underground cisterns, reservoirs and channels clean to assure potable water for the residents above. Melisurgo carried the pozzaro piggyback, much like Jean Valjean did with Marius in "The Intestine of the Leviathan".

In a scholarly manner, they divided the subterranean city into five "water districts: San Lorenzo, Banchi Nuovi or Spinto Santo, Montecalvario or Carità, San Ferdinando, and Regi Studi, "which do not correspond to those districts above". They counted 3,350 well shafts or "pozzi" for the Bolla aqueduct alone!

This meticulous research, even though limited to only the ancient water system, produced a priceless reference valued and used by modern day students of Naples’ sottosuolo. Since Melisurgo’s two-year study in the late 1800’s, very little has been done to expand his work despite the worsening of conditions beneath the city.

In 1892, problems began to multiply. The city’s sewer system had become unable to handle the increased volume of water. The Minister of the Interior appointed a commission of engineers to "study" the Naples underground. In the 1930’s the daily newspaper, "II Mattino" reported with increasing frequency stories of cave-ins, sink holes and washouts all over the city. In 1934 the Naples Engineers Union decided to study the relationship between the damage being caused and the cavities below.

With the beginning of World War II came the reopening of the artificial caverns to the city above. Massive aerial bombardment send the population scurrying in search of shelter. Tens of thousands of persons spent anxious hours, some even weeks at a time, in the caves and cavities beneath the city. Work was hurriedly undertaken to enlarge tunnels and old aqueducts into passageways to connect the huge the caverns located some 40 meters below the city. The drastic emergency measures resulted in the fragmenting and chopping up of the ancient labyrinth. Prior to these changes used to create the bomb shelters, it was possible to easily wind one’s way from one part of the city to another using the maze of tunnels, galleries and narrow aqueducts.

In 1956, a citizens’ committee called for an investigation of the crumbling ruins and damage that resulted from the intensive bombardment. They recommended a "complete rebuilding and restoration of Naples’ historic center." This was the beginning of "the sacking and looting of Naples".

Speculators and building contractors began covering the hills of the Vomero and Posillipo in an unregulated, graft-ridden, ferro-concrete construction boom. No one took into consideration the ancient hollow underground beneath the frantic building going on above. In 1967, with problems worsening, the local press again campaigned, in a series of articles, about building underground parking garages. This time a Naples daily newspaper "L’ Unità" took sides with a lengthy series of investigative articles that forced the city administration to appoint a "Bureau of the Underground".

Then in May of 1969, the city appointed a second commission to study the situation below. They incorporated the findings of the previous committee and wrapped up their work in 1972. In their final report they again strongly criticized the speculators and developers for their reckless and uncontrolled building. They completed a census and mapping of a total of 150 cavities which totaled 260 thousand square meters of hollow space. The first commission located only 13.

In 1975, the Regional Government of Campania passed two laws (numbers 30 and 38) to address the underground problems in the inner city. Their assistance, however wound up going to outlying areas which had also suffered heavy damage. These areas, from 8 to 15 kilometers north of Naples, included Grumo Nevano (12 city blocks damaged, 8 streets caved in), Frattamaggiore. Cardito, Afragola, Arzano, Casavatore and Casoria. And here is where governmental intervention and assistance has stopped. Today, the same Ufficio Sottosuolo or "City Bureau of the Underground" is the center for much debate and discussion and does occasionally file charges, but it lacks the funds, equipment and manpower to be very effective.

The only ones to carry forth

Melisurgo’s work of the late 1800’s are a few groups of private

individuals with a passion for the mystery of Naples’ sottosuolo. These

include the "Centro Speleologico Meridionale" or Southern

Speological Society and the Naples branch of the "Club Alpino

Italiano: or Italian Alpine Club.